The Japanese Garden

The modern japanese landscape design

In Japan, the garden has always been defined as a dialogue between man and nature and the niwashi, master gardeners, have always created new gardens with respect for tradition. It is curious to see how the Japanese concept of tradition is inherent the type of innovation: there is no tradition of innovation. The article analyzes how some compositional elements of the classical tradition of the Japanese garden have been reinterpreted, interpreted or simply re-proposed in some contemporary creations present in Japan. These are not only the creations of Japanese landscape architects but, on the contrary, also of works by Western authors who, successfully, have embarked on the arduous path of garden.

“The Japanese landscape” is not just nature, not simply spontaneous nature, as the literal translation of the Japanese word nature – shizen – would lead us to believe. The Japanese garden has always been nature created by man. It belongs to the realm of architecture and is, to put it better, nature as a form of art “(Günter Nitschke, 1999). In Japan, the garden has always been defined as a dialogue between man and nature and the niwashi, master gardeners, have always created new gardens with respect for tradition. It is curious to understand how the idea of innovation is inherent in the Japanese concept of tradition: there is no tradition without innovation. To the call of the signs and geometries typical of the classical garden is added a continuous and always new expressive research which, for decades now, has also drawn from the Western repertoire. Many authors, such as Arata Isozaki, Bruno Taut and Alessandro Villari agree that modern Japanese landscape design has undergone Western influence and fashion, but the authors themselves agree that, very often, the same classical tradition of the Japanese garden has become, for the Western world, an example to be imitated and reread in a modern key. And it is on these issues that the concept of innovation-tradition will be explored below. We will analyze how some compositional elements of the classical tradition of the Japanese garden have been reinterpreted, interpreted or simply re-proposed in some contemporary creations present in Japan. As we will see, these are not only the creations of Japanese landscape architects but, on the contrary, also of works by Western authors who have successfully undertaken the arduous path of the garden.

The Japanese garden

The classical theory of the Japanese garden is generally based on three compositional principles that define the spatial and volumetric organization of the landscape: the miniature landscape (shukkei), the borrowed landscape (shakkei) and the dry landscape of contemplation (karesansui). In addition to understanding the meaning and practical implications of these compositional principles in landscape design, we will also mention the technique of sumikake (corner connection) and the way in which, in the Japanese tradition dating back to the Edo era (1603-1868), the framing of any natural image is organized, the so-called foreshortening. These last two compositional aspects will allow us to understand some of the design choices illustrated and will be useful to define the completely Japanese way of observing the landscape, whether it is an urban environment or a glimpse of nature.

The Edo period (1603-1868) it has been a long and admirable cycle of growth and consolidation of Japanese aesthetic standards.

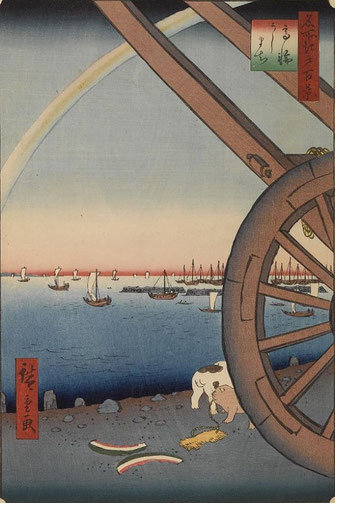

It is in this period that the great artists worked of ukiyoe (il cosiddetto mondo fluttuante), come Hokusai (1760-1849) e Hiroshige (1797-1858), ed è in questi secoli che l’arte pittorica di organizzare il paesaggio o un qualsivoglia soggetto naturale, come un fiore o un pesce, ha raggiunto la chiarezza compositiva che oggi apprezziamo.

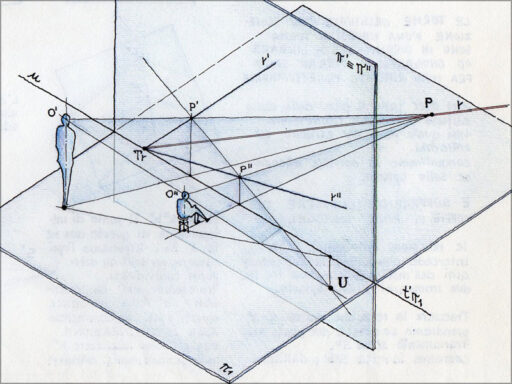

Cercando di definire in modo accademico e schematico le caratteristiche che definiscono la cosiddetta visione a scorcio del soggetto, potremmo asserire che the portrait subject is not in the center of the frame, it is often in the background and, at times, we observe an element that comes between us and the subject himself. This totally Japanese way of organizing the shot determines in the observer a increase in participation to the scene portrayed; this is because curiosity and the will to see the hidden part of the subject prevails; moreover, more often than not, one gets the impression that what comes between us and the subject originates behind us and, therefore, physically accompanies us inside the image itself.

Looking at Hiroshige’s painting on the side, it is evident that the artist’s compositional effort is aimed at the full participation of the observer in the scene portrayed. One has the impression of observing the scene crouched under a cart which, of course, continues above and behind us. This compositional device allows our subconscious to believe that it is inside the image. The boats in the distance, the subject portrayed, are in the background, not in the center of the image and partially hidden by the cart wheel. The whole composition increases our participation in the image through two particular moods: the curiosity to see what is hidden, and the suggestion of feeling an integral part of the frame.

Looking at Hiroshige’s painting on the side, it is evident that the artist’s compositional effort is aimed at the full participation of the observer in the scene portrayed. One has the impression of observing the scene crouched under a cart which, of course, continues above and behind us. This compositional device allows our subconscious to believe that it is inside the image. The boats in the distance, the subject portrayed, are in the background, not in the center of the image and partially hidden by the cart wheel. The whole composition increases our participation in the image through two particular moods: the curiosity to see what is hidden, and the suggestion of feeling an integral part of the frame.

To further clarify this completely Japanese way of framing the landscape, let’s try to observe the same portrait subject both with a typically Western framing and with a framing defined by the foreshortening of the subject. Photos 2 and 3 depict the Murina-an garden (Kyoto) designed by Ogawa Jihei, a well-known landscape painter of the Meiji era (1868-1912). It is a work that has undergone English influence not only in the organization of the hilly volumes, very similar to the full and empty scholars of the English landscape garden, but also in the architecture of the house, which is clearly Anglo-Saxon style. Beyond the composition and history that distinguish this garden, we observe how the first photograph (photo 2) has a clear western setting: the stream portrayed is in the center, all the other compositional elements act as a frame to the subject and nothing prevails over what it was decided to portray. By analyzing the figure graphically, we can assert that, in this case, the image can be defined and schematized through a perspective study with a central vanishing point: the vanishing lines converge towards the center, which always houses the portrait subject.

It is the opinion of the writer that this graphic setting can be defined as symmetrical and equal.

Taking up what we have previously asserted about Hokusai’s pictorial work, the subject is not in the center but, on the contrary, is shifted to the right and is in the background; in addition, a maple branch, which naturally originates from a plant behind us, accompanies us inside the image and partially masks what is portrayed beyond the leaves. We are more curious to continue the journey in the image to be able to admire the river and the hills. Compared to the previous photograph, this image can be called asymmetrical and dynamic.

If in the so-called static gardens of contemplation, where there is an evident preferential point from which to observe the garden, one can imagine an easy spatial organization with a glimpse of the subject, in the numerous classic strolling gardens there remains the doubt of how this compositional character can be realized. In this regard, we recall the garden of the Imperial Villa Katsura (17th century) in Kyoto, considered, rightly, one of the greatest examples of enshugonomi (literally in the manner of Enshu Kobori, a well-known architect of gardens of the early Edo period) as well as one of the most important Japanese roji (tea garden).

As Arata Isozaki teaches and as, before him, Bruno Taut had exposed in his travel diaries, the organization of the space around the villa is based on the principle of strolling to reach the goal, which, in the case of the present garden, consists of various tea ceremony houses. You walk along the paths and streets of the garden as if it were a pilgrimage between one tea house and another, between one architecture and another.

This is one of the gardens in which the beauty of the work is inherent in the walkway and movement from one area of the landscape to another. Along the paths the view of the landscape is often hidden by vegetation and not infrequently the walkways are so inaccessible that we have to look down on our steps, taking our attention away from the scene that surrounds us. All this is wanted and sought after by the designer. In fact, our gaze returns to the landscape only in those points of the garden, which we could still define preferential points of view, studied and organized by the landscape architect drawing from the classic technique of foreshortening the subject. After having traveled a long path immersed in a bush that obstructs the view of the lake, after having followed paths, sometimes “naturally” bumpy, after having glimpsed and imagined the architecture and the lake among the leaves of the trees, we arrive where the path takes a slight curve to the left and with astonishment the scene that opens up to our eyes is clearly organized foreshortening.

The tea house we admire is partly hidden by a pine which, in turn, is in the background compared to an ancient lantern which attracts our attention. Furthermore, the tea house is not aligned with our progress and is oriented towards another direction that points, in all probability, towards an element of the landscape that we cannot see because it is masked by other trees and islands. Our curiosity to see what can be admired from such a fascinating architecture is such as to induce us to continue the journey to reach this house from where, with surprise, we will observe another scene organized with the foreshortening of the subject, which will feed once again in us the curiosity to see what is partially hidden.

All this expands the space, increases the depth and makes us participate in the landscape.

The corner connection and foreshortening

Parallel to the image organization technique described above, there is the so-called corner connection (sumikake), which consists in arranging the walkways and the building lines along a zigzagging line. This proceeding along lines perpendicular to each other allows us to always create new views since, following the change of direction, previously hidden and unimagined landscapes open up. Photo 5 shows some glimpses of the long zigzagging that characterizes the entrance to the Koto-in temple (16th century), which is part of the Daitoku-ji complex in Kyoto. It is evident how in such a limited space the sumikake technique is able to enormously expand the surfaces and how it allows to always obtain new views. Note again how the opening onto the garden that can be admired at the end of the last path is organized with the foreshortening technique of the subject just described.

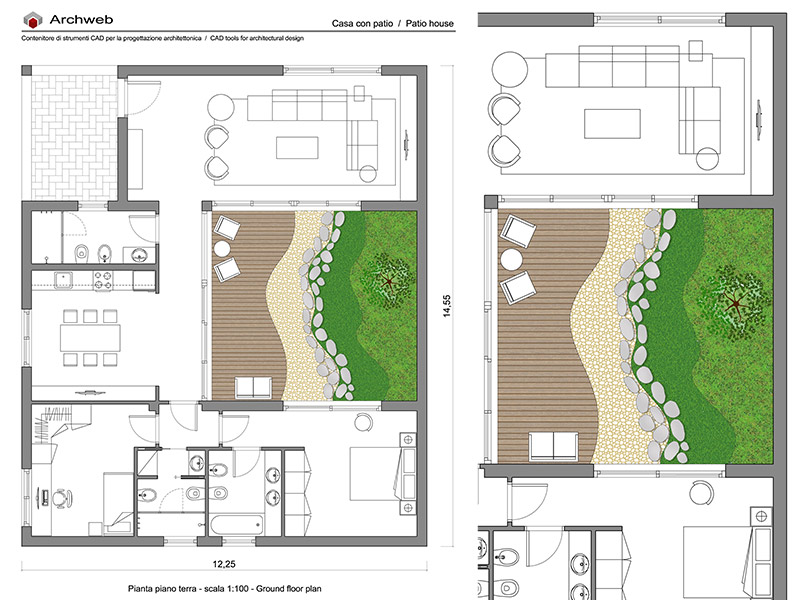

The entrance to the Honpuku-ji Temple (Shinto temple dedicated to water) designed by Tadao Ando in 1991 on Awaji Island in Osaka Bay. In this case, however, the well-known architect wisely introduces the curved line, a graphic aspect not present in the classical tradition of the Japanese garden.

The zigzagging of the first part of the walkway conveys in a gentle curve that progressively reveals the panorama beyond the white circular wall: the large water basin of the water lilies which, in addition to being an unexpected element of surprise, is also the roof of the temple below.

See the project also available in dwg format … >>

These two compositional aspects, the foreshortening of the subject and the sumikake, are typical elements of Japanese aesthetics and are still today reinterpreted and interpreted in modern landscape creations, which we can include in each of the interpretations of the landscape proposed by Villari : the miniature landscape or garden collection (shukkei), the borrowed landscape (shakkei) and the dry landscape of contemplation (karesansui).

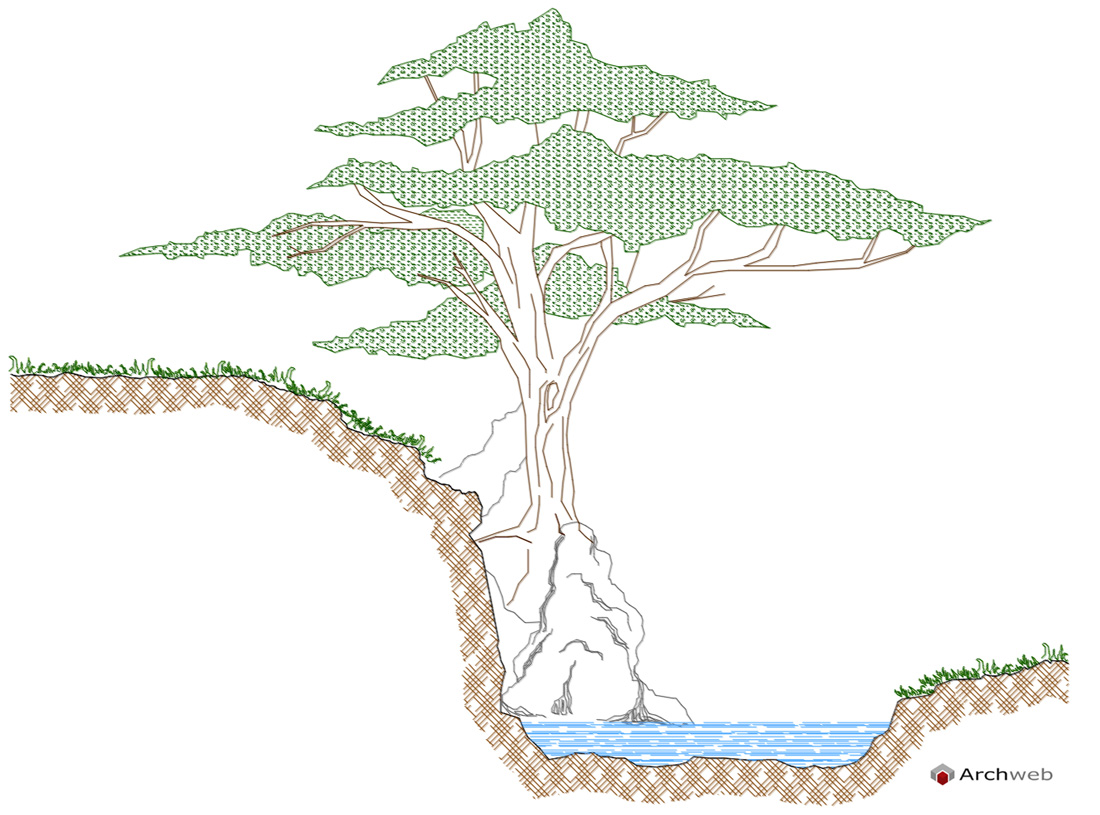

Paraphrasing Villari “… shukkei (from shuku to reduce and kei landscape) is the technique of miniature representation of the landscape. This particular expression is typical of the gardens built during the 17th and 18th centuries; Katsura … “, which we learned about in the previous dissertation on the foreshortening of the subject,” … is a clear example of shukkei, a narrative text on Japanese territory, a sort of metaphor for some of the most famous landscapes, an ideal place where to make endless pilgrimages. A garden created to be crossed, a kaiyu shiki teien, literally a garden for strolling… ”. The theme is that of the journey where the story, made up of many chapters, different views and numerous tea houses, is perceived thanks to the time unit of the visit. As in Katsura, also in many other historical Japanese gardens it is observed how “… the representation of easily identifiable archetypal landscapes, unconscious heritage of memory, facilitates the reading and interpretation of the natural landscape …” (Villari, 2003). An example is the large sand cone of Ginkaku-ji which represents the profile of the well-known Fuji-yama, the lakes of Kinkaku-ji or of Katsura itself, reminiscent of seas dotted with islands, the rocks of Ryoan-ji or various sub-temples of the Daitoku-ji, which evoke images of mythical or real mountains and, again, animals of the Japanese tradition such as the crane, the turtle and the carp.

Many examples of contemporary landscape design according to Villari “… present narrative texts, made up of sequelae, hierarchies and rhetorical figures. … the observer is invited to symbolically appropriate the repertoire of images, symbols and meanings to be included in the list of their experiences “.

The carp, a typical animal of the many traditional Japanese gardens with lakes, is certainly the main theme that links Martha Schwart’s work to Nexus Fukuoka International Housing. A large group of internationally renowned architects, coordinated by Arata Isozaki, was involved in the redevelopment of a large district in the city of Fukuoka in southern Japan in the 1980s and 1990s.

Martha Schwart was asked to study and create a connective tissue able to unite all the buildings and architectural structures put in place during the works. Schwart’s winning idea was to reinterpret the shukkei in a modern key, narrating the passage of some carp through the various buildings (photo 8). The resulting fluid dynamism goes well with the memory of carp in historical Japanese gardens which, when the hands clap, flock to the guest. Seen from the top of the buildings, the park assumes that microscale typical of the shukkei: from many tens of meters high those large mounds of rock and grass are reminiscent of carp in motion, the large bamboo and palm trees evoke rushes of the lake and, as in a modern karesansui, the color of the pavement recalls the great sea of sand of Ginkaku-ji.

Umekoji Park di Kyoto

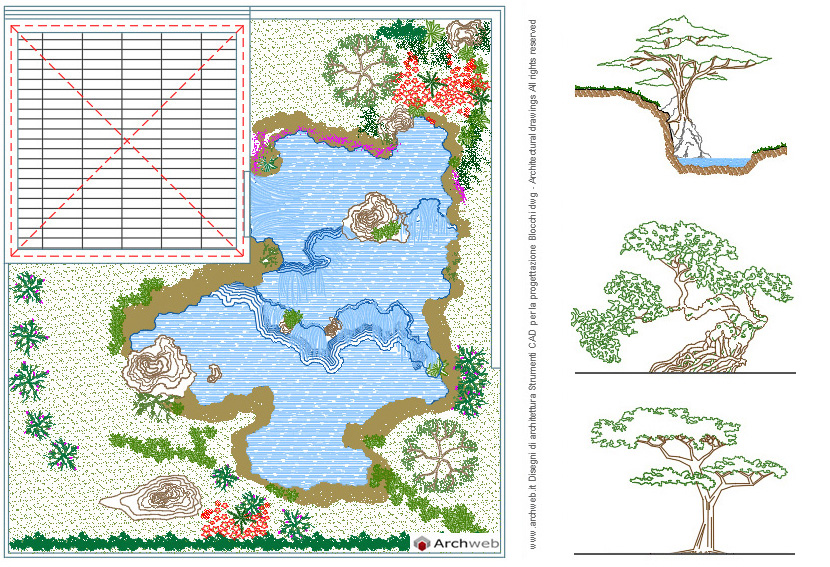

Another example of modern shukkei is the Umekoji Park in Kyoto, built around 2000, as a reminder of the history of the capital Kyoto (main photo). A great international design competition saw many of the most important landscape architects of our time try their hand at the reinterpretation of the classic garden. Of all the ideas received, the winning one turned out to be the revival of the shukkei reinterpreted through new proportions and thanks to the use of modern and technologically advanced materials.

Kyoto’s Umekoji Park, like Katsura, is a series of landscapes drawn from the unspoiled nature of Japan. Water is the common thread that binds the whole story: it all starts from the waterfall, then continues through the streams, rivers with large bends and finally reaches the calm and placid sea full of ravines and peninsulas that stretch into the his mirror. Only the rigidity of the form of some modern elements and the use of technological materials such as aluminum and optical fiber make it possible to understand that this is a contemporary work.

Paraphrasing Villari again, the technique of“…shakkei, literally the imprint of the landscape, it consists in establishing a visible link between the garden space and the surrounding landscape. (…) The shakkei is not limited to a simple visual relationship with the horizon but, from time to time, uses the landscape as a material, with the same criteria with which stones, gravel, vegetation and water. Thus mountains, hills, woods, lakes, swamps, waterfalls and even elements of architecture outside the garden find the right place… ”.

In the classical history of the Japanese garden there are numerous works that have drawn, thanks to the shakkei technique, images and natural elements external to the property. Among these we remember the well-known Murin-an, Etsu-ji, Koetsu-ji and Kogen-ji gardens, which have “framed” the profiles of some Kyoto mountains making them become compositional elements of the garden.

The contemporary garden of the Research Center for Japanese Garden Art of the Kyoto University of Art and Design, designed and built about ten years ago according to the most classic shakkei tradition, is a clear example of how the space can be extended almost to infinity by emphasizing images and elements of the surrounding landscape (photo 9). In this case, it is again one of the many mountains of Kyoto that becomes the protagonist of the garden. Photo 8 highlights how the design of the work drew not only from the traditional shakkei technique, but also from the classic way of organizing the foreshortened image.

Another example is the contemporary shakkei Kyoto Station Plaza designed by Hiroshi Hara in 1994. In the early nineties Hara won the competition for the new construction of the Kyoto station which involves, among others, Tadao Ando, Kisho Kurokawa and James Stirling. Drawing from Villari’s description of it, Hara’s project is a “… hellish architectural machine, two large slats parallel to the tracks enclose a large hall, of enormous dimensions, creating a large void covered by a skylight of two hundred meters in length for about seventy in height. (…) crossing the hall you are transported, with complex escalators, to the roof of the building where one of the most interesting places of the entire station is located … “.

It is a large hanging square that serves as a panoramic terrace over the entire city of Kyoto. Like large frames, the structures of the perimeter frame well-defined and expertly identified views of the city. As Villari himself admits, it seems that the landscape of the city of Kyoto is projected like a film on the border walls of the square, and that Hara’s project is a modern shakkei in the city of the Japanese historical garden par excellence.

These are some examples of modern creations that have drawn from the classical tradition of the Japanese garden, extrapolating the true compositional meaning and aesthetic implication of a culture that has always seen the discourse on the garden in the dialogue between nature and man.

dr. Agr. Francesco Merlo

Master in Landscape Design and Green Areas – University of Turin

recommended cad drawings

DWG