From cohousing to social housing

Forms of shared living

1. 1. Shared living: solutions for social development.

How social change affects housing models

In recent years, the “housing question” has been at the center of many debates in which the focus has been on the reinterpretation of the term “living”.

Economic and social policies have seen representatives of the Government and Administrations focus on the topic in order to provide satisfactory answers. The primary objective was to ensure, in shared social housing, the same quality as traditional housing models on the market.

Starting from 1960, the new reality of cohabitation took hold in Denmark and enjoyed growing success, up until today, a period in which the flexibility and temporariness of residence are characteristics of primary importance. A concept of living therefore matures that declines towards different nuances: the hybridization of spaces, the connection and sharing of resources, social commitment, group activities and participatory decision-making processes.

Furthermore, due to today’s socio-economic situation, there has been a rapid transition from permanence to the transitory nature of living. We are increasingly faced with the habit of conceiving space in a changing way and the uses linked to it different depending on contingencies. Flexibility thus becomes a fundamental requirement of this type of home and is established in the typology (wide and varied offer) and in the technology (substitutability, adaptability of the components) applied to it.

The changes of a social nature correspond to the change in the relationship between spaces, people and inhabitants so that environments which until yesterday had a precise function and were experienced according to the rhythms of time, today become places of passage with an undifferentiated function. The articulation of the basic patterns of living follows the changes in the life experience of the individual subject, thus making the architectural discipline unstable and continuously changing. This concept, which is becoming increasingly popular today, does not allow designers to follow a pre-established model but puts them in a position to prepare a housing program that can take on different nuances depending on the case.

Among the phenomena that have caused these changes, there are also globalization and sustainability. The first led to a contraction of times and an expansion of spaces, with consequently faster rhythms and changes in daily habits. Sustainability, on the other hand, has faced users and designers with the problem of limiting consumption and saving energy.

2. I live together ergo sum: inter-family realities compared

Let’s now see how social changes and urban transformations have pushed users to seek housing models different from traditional ones. These are life solutions that tend to reconcile the public dimension of the community with the private dimension of the individual.

Here are some examples:

- Common

Residential communities of people who share both spaces and life choices. - Solidarity condominiums

They do not presuppose cohabitation but cooperation between independent families that share activities and values. - Territorial communities

It is a larger reality, not necessarily linked to a shared residential building, but to entire neighborhoods in which the inhabitants create social networks and solidarity. - Ecovillages

Usually they arise in rural areas, their inhabitants choose resources, food, care for children and aspire to a return to nature and a healthy life. - Cohousing

Communities of people open and free from ideological or religious ties, in which private and common spaces coexist. The groups organize through participatory planning, the identification of collective services and the management of internal activities. - Social housing

Forms of facilitated residence within which residents establish social and collaborative relationships. Nowadays, social housing is changing its original connotation, affecting not only the weaker sections of society but also people belonging to various age groups united by the interest in developing sociality and supporting choices based on economic and environmental sustainability.

3. Cohousing and social housing: common characteristics and differences

As regards specifically cohousing and social housing, these are residential models that aspire to provide users with “additional” spaces that can be exploited in the most varied ways to create sociality and utility.

These are two very similar housing realities but different in some aspects, which are often confused. For both, the idea of sharing is at the base: the choice to sacrifice private space in the apartments in favor of common areas that encourage socialization.

However, some aspects are different: cohousing is a smaller reality, born from private projects of a few people who often know each other and share values and daily habits. Social housing, on the other hand, arises from purely economic needs, offers homes at controlled prices and develops with the support of medium-large sized associations and foundations. Location also distinguishes the two realities, in fact social housing all arises in a more or less dense urban environment, while cohousing can develop in the city and also in extra-urban contexts.

From the point of view of the planning process, the two realities differ in some aspects, first of all the level of “participation” of the future users: cohousing places among its five fundamental points, the participatory process which sees the cohabitants in a equal and active position in choices and decisions for the organization of cohousing.

The situation is different in social housing where specially trained professional figures proceed with the design based on the interest in satisfying the needs of users who however cannot participate in the preliminary phase.

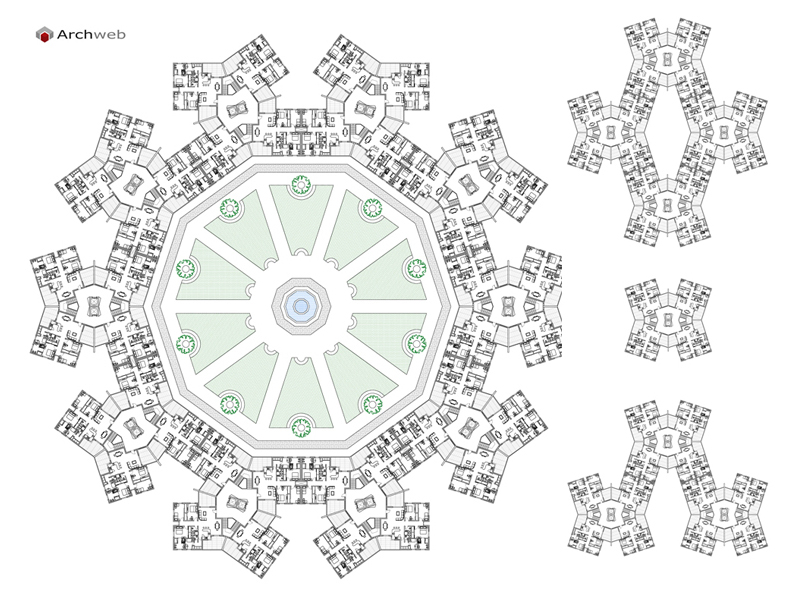

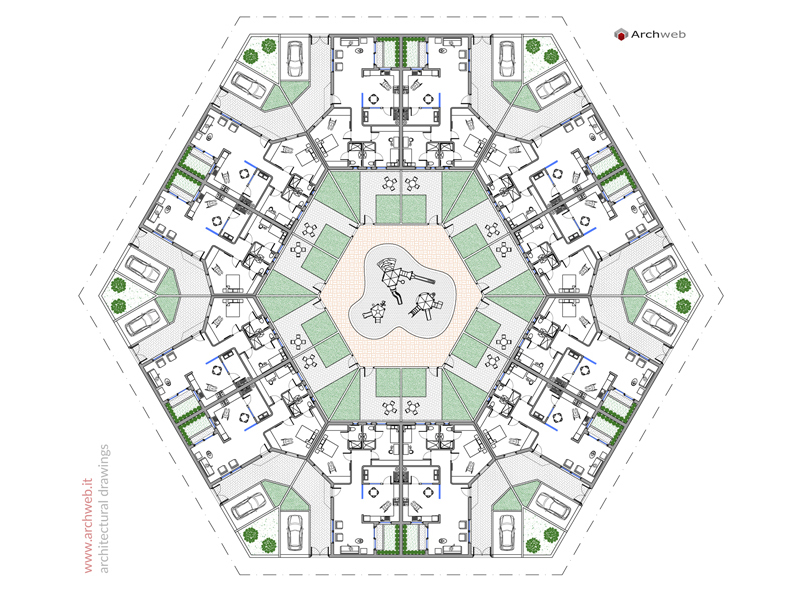

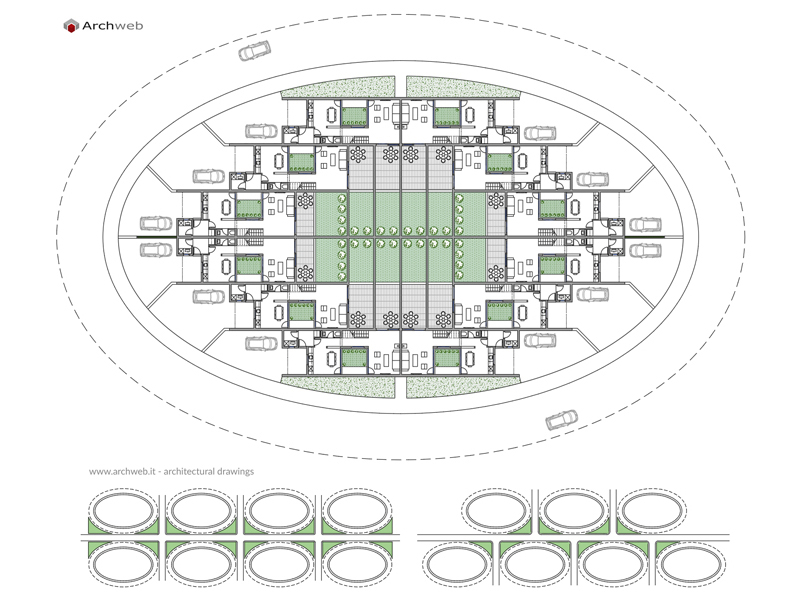

As regards the spatial conformation, it manifests itself as the mirror of the needs of the users: while the private apartments are small in size, the common open areas and the collective closed environments which host additional services (gyms, playrooms, laundries) gain space , taverns, communal kitchens, relaxation rooms…) and which encourage individual savings and greater socialisation.

4. Cohousing: a possible alternative to urban life

There are various types of family realities and they all have a common prerogative: what defines “being a family” is the feeling of familiarity not necessarily limited to the regulated social context.

The term cohousing from the English “community housing” establishes itself as a housing reality with the aim of solving the problem of social cohesion and the recovery of community life. Although cohousing experiences do not follow rigid rules, there are some characteristics that European, American and Australian cohousing have in common.

First of all, the participation and intentional planning that sees future residents active from the first moments of the planning process in the common choice of the place in which to live, in the organization and management of the spaces. At the base there is a hierarchical structure in which decisions are made in a collegial way, excluding the figure of the leader.

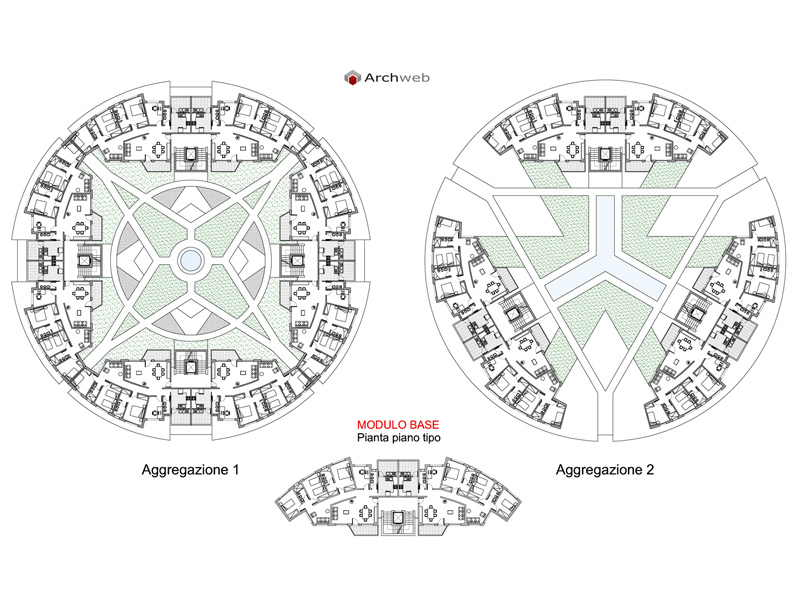

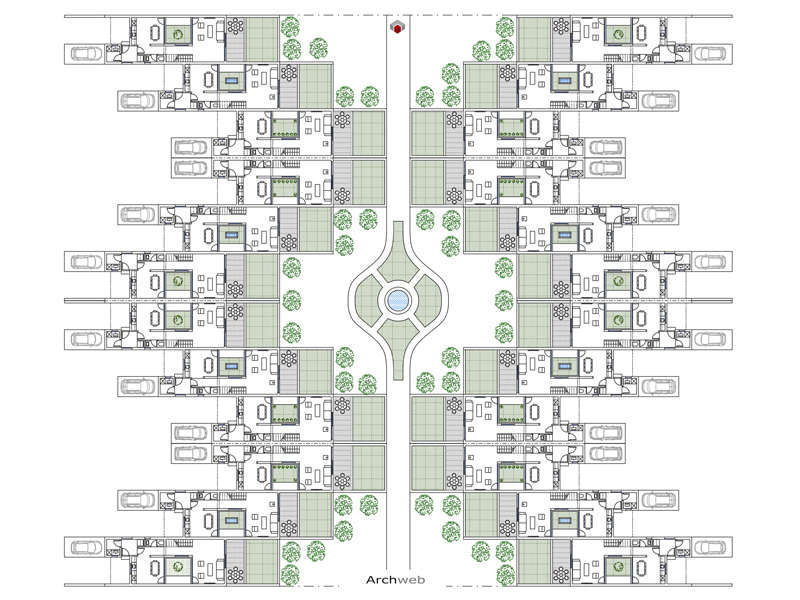

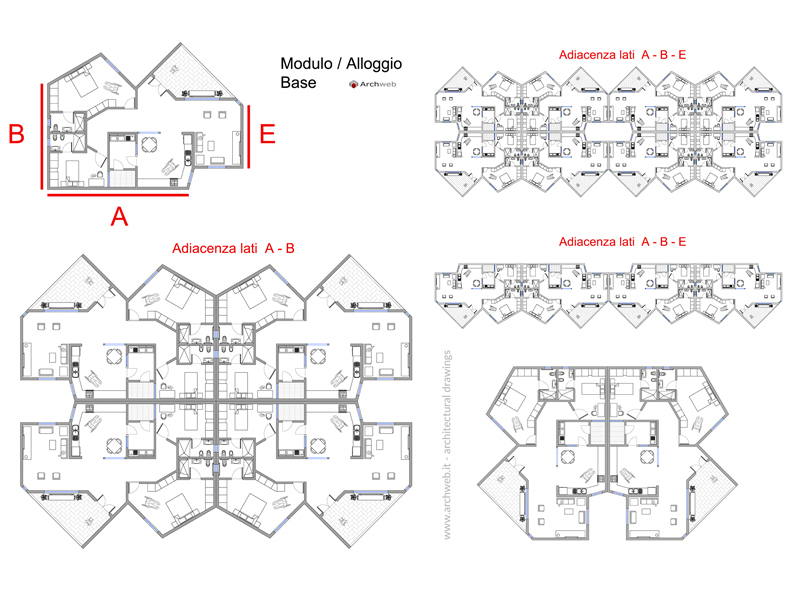

As for the architectural style, similar to most cohousing, it includes single-family houses or apartments, usually located along a common road or around a central courtyard. Fundamental importance is given to the common spaces which occupy a large part of the designed space, integrate the private apartments and are favored over them.

The common services ensure social and economic advantages, in fact, even if the initial cost of building a cohousing is usually higher than that of a traditional home, at a later stage the users will begin to notice the considerable economic savings thanks to the use of the common goods (computers, sports and gardening tools, cars, bicycles, etc.) and energy saving choices.

5. Social housing: development, the Italian case

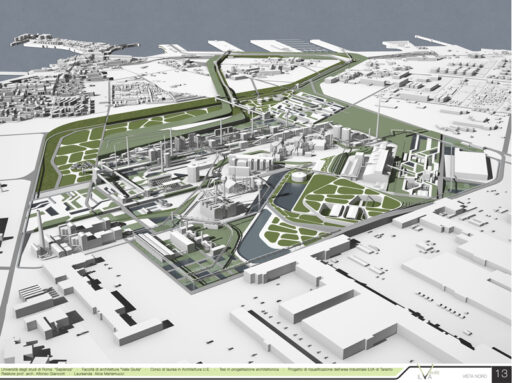

From the analysis regarding the development of social housing in construction, it appears clear that it is closely linked to changes in lifestyles and urban spaces. The city changes as it is not just a collection of homes but a place of sociality, a venue for meetings and exchanges between its inhabitants. The concept is gaining ground that collective spaces not only find definition in squares and courtyards but also in actual portions of buildings that become the fulcrum of the social and cohousing project: relaxation rooms, communal kitchens, playrooms and gyms. Therefore the challenge that social, economic, political and institutional operators must accept is that of imagining, planning and devising a response to the housing need, which takes into account the social factor as decisive. Social housing today represents a service of general economic interest and must meet the requirements of adequacy, safety, healthiness, environmental sustainability and energy saving.

Nowadays, the old council house has been transformed into a “social house”, a dwelling made up of natural materials, which uses technologies aimed at energy saving and which aims to provide the best thermal and vital comfort to its users. As regards the Italian situation, in the last ten years there has been a new explosion in the demand for housing at controlled rents with an expansion of users.

The increase in housing costs, the precariousness of work, and consequently the lower income, have increased the demand, however the prejudice towards the term “social” and the absence of a national law on the matter do not favor the affirmation of the phenomenon also hindered by urban planning regulations which see expansion as a rule that continues to have the best over the redefinition and recovery of the existing city. Consequently, Italy has a low percentage of public residential construction, with 4% recording the lowest percentage of public housing compared to the 20% on average at a European level.

6. Case studies: the Turin reality

In recent years in Turin the desire to live in cohousing is spreading among some groups of citizens. It is a slow process, which requires considerable time and commitment but which has proven to have a good outcome.

In the city scene, some associations stand out that are committed to the development and diffusion of this housing alternative, a well-established example of which is the Coabitare Association.

6.1 Cohousing Numero Zero – Coabitare Association, 2012

It was the first real example of cohousing in Turin, sponsored by the “The Gate Porta Palazzo” project aimed at redeveloping the urban area.

Located in a multi-ethnic neighborhood of the city, between old generations of Turin and new generations of foreigners, it stands out from other cohousing projects because it starts from the urban center and from the initiative of a few highly motivated people.

Starting from the renovation of an old building in Via Cottolengo n.2, today we have arrived at the creation of a simple and functional housing model which, in addition to ensuring a comfortable and economically sustainable lifestyle, contributes to social development.

As regards the structural and technological choices, the designers moved in a manner consistent with the desire for social and environmental sustainability:

- Morphological conservation of the historic building

- Spaces flexible over time

- Distribution of internal environments with a view to social development

- Accessibility of common areas:

– two multifunctional rooms;

– a laboratory/cellar;

– a courtyard on the ground floor;

– a terrace at high altitude;

– a technical room.

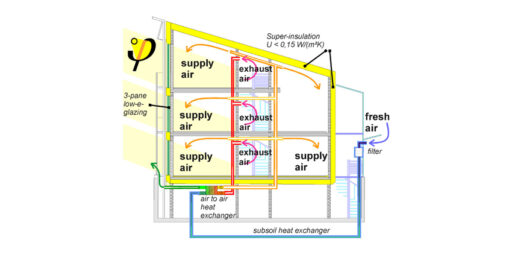

- Sustainable choices:

– good insulation of the casing;

– high thermal performance windows;

– thermal solar panels;

– low energy consumption (energy class B).

- Rules shared by cohabitants

Source: www.corriere.it – www.cohousingnumerozero.org

To date, the building retains its old structure which has been given new light. It is a successful example of cohabitation in the city and has contributed to the slow and progressive rehabilitation of the entire neighborhood.

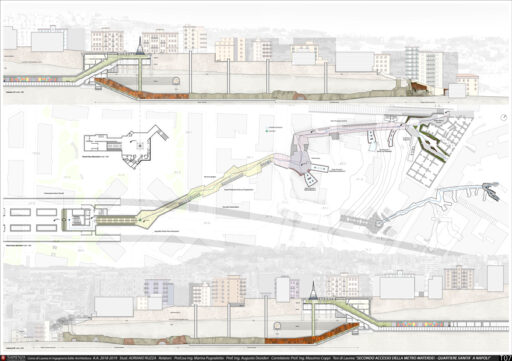

6.2 Common Places – Company of Saint Paul – Pious Office

As regards social housing, in recent years there has been a dramatic increase in the demand for rent-controlled apartments in the Piedmont area and in the city of Turin.

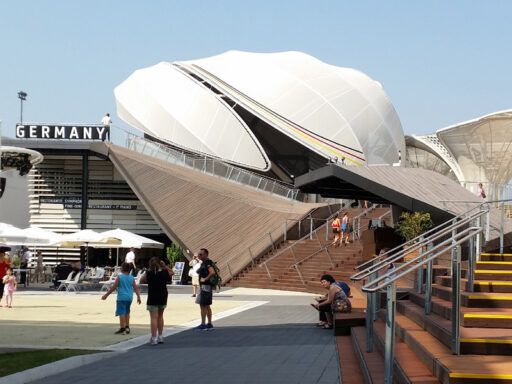

One of the last concrete examples of social housing in Turin is represented by Luoghi Comuni, a project belonging to the Housing Program of the Compagnia di San Paolo with the contribution of the Pio Office. It is a temporary residence that occupies an area of 2200 m2 distributed over five levels above ground which has set itself the objective of redeveloping the territory from an architectural and socio-cultural point of view.

The project was a real driving force to encourage the interaction of the inhabitants of the neighborhood and encourage its valorisation; in fact, there were many social initiatives and events that took place within it.

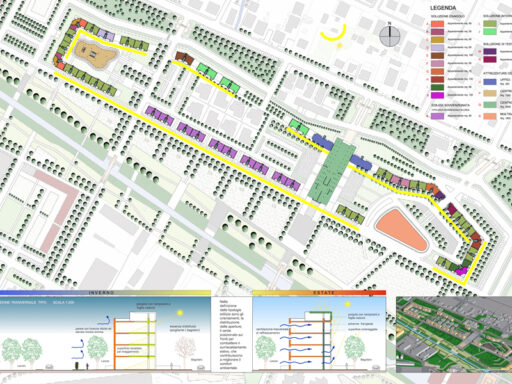

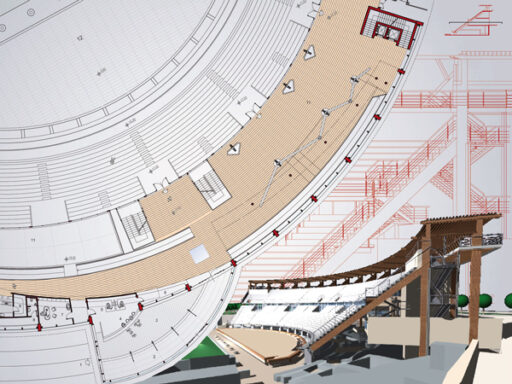

Of primary importance were some architectural choices that allowed development and social exchange:

- cohesive relationship between building and context (opening of the built block to the surrounding open space);

- elimination of pre-existing diaphragms and creation of new socialization spaces;

- increase in the permeability of the building with respect to the urban fabric in which it is located;

- functional mix of residence and commercial establishments;

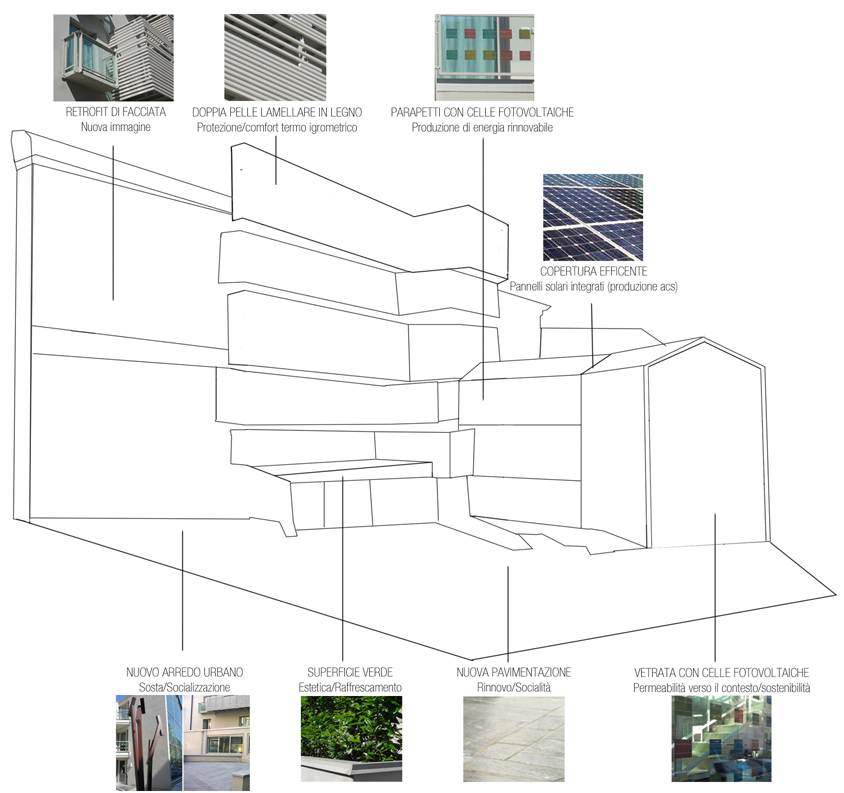

- facade retrofit (attractor pole).

The spaces of the building are conceived following the rules of flexibility and temporariness so that they are modeled on the needs of ever-changing users. The common areas are designed in order to be used by those who live in the building but also by the citizens of the entire neighborhood who thus perceive social housing as a real attraction pole.

No less importance was given to the aspect of economic savings and respect for the environment with sustainable technological choices.

Finally, the study of the open space at high altitude and on the ground floor allowed for its refunctionalization aimed at improving habitability and connection with the urban fabric.

The open space on the Ground Floor

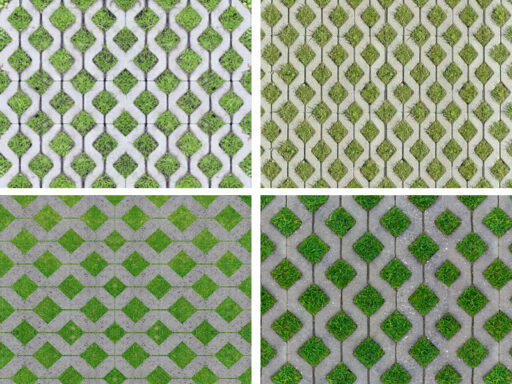

- new paving of the pedestrian area in front of the building;

- insertion of new street furniture;

- demolition and reconstruction of the lower sleeve;

- insertion of vegetation (aesthetic and cooling function).

The open space at high altitude

- full-height glass in the restaurant;

- lamellar structure on the facade guaranteeing privacy and internal shading;

- photovoltaic cells inserted in the glass parapets of the balconies.

Photos taken from:

www.luoghicomuni.org – www.programmahousing.org – www.compagniadisanpaolo.it

Graphic schemes taken from Chiara Del Core’s Master’s Thesis “From cohousing to social housing: forms of shared living” – Rel. Alessandro Mazzotta, Eliana Perucca – Polytechnic of Turin.