Biophilia: the new living spaces

Interview with Stefano Serafini

The concept of sustainable architecture is an important theme for new concepts of both public and private space. We asked Stefano Serafini, director of research of the International Society of Biourbanism (www.biourbanism.org) active on research and debates dealing with biophilia in architecture and urban planning in Italy and abroad, to focus on key points for the design biofilica.

[..] our cognitive system and how it, in its reaction to the environment, involves all the other systems of which we are composed, from the endocrine to the social one [..]

Below is the interview for Archweb readers.

What does the concept of biophilia represent for you?

Indeed, biophilia understood as an attraction to all that is living is a hypothesis developed by a biologist, Prof. Edward O. Wilson, in turn influenced by the thought of Erich Fromm (his book Psychoanalysis of love. Necrophilia and biophilia in humans is from 1971), the psychologist and sociologist who believed that there were two opposing forces in the psyche and in society, one that pushed towards life, and one towards death. Wilson presented his idea to the public in the early 1980s as an explanation that could account for a range of observable behaviors. Ten years later he also tried to give an evolutionary foundation to this hypothesis, and other authors have moved on this foundation, first of all Stephen R. Kellert, whose book Biophilic Design (2008) is one of the best known references.

When I started dealing with biophilic design, a dozen years ago, the theme was still practically esoteric. I came here by chance, knowing what would later become a close friend, Professor Nikos A. Salingaros, who is somewhat the father of this way of integrating “nature-friendly” cognitive structures into architecture. Salingaros, among other things, is the person to whom we owe the drafting of Christopher Alexander’s absolute masterpiece, The Nature of Order, in 4 volumes.

And the biophilic design of Salingaros is in some way the development, the specialization of ideas contained in Alexander’s work, an attempt to explain, for example, the objectivity of spatial conditions such as “wholeness” and why they make us feel good . I had conducted research on the epistemological status of non-Darwinian theories and e.g. I had edited the Italian edition of Antonio Lima-de-Faria’s work, Evolution without selection. Self-evolution of form and function, and the contact points that came on in my mind were many. There had to be a deeper foundation of evolutionism or a socio-psychological theory to explain the fact that almost all human beings prefer certain spatial structures to others, and it seemed to me that the direction to follow was precisely the isomorphy between cognitive systems organic and natural in general.

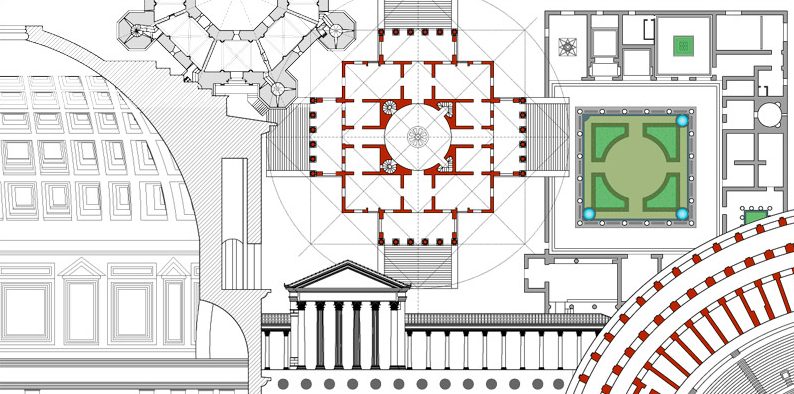

Today I believe that this isomorphy is a fact and that, as Alexander already understood, it has to do with “sub-codes”. These hide and compose themselves in a vast number of codes, let’s say, visible, to which our biological and neurocognitive systems “respond”, making us perceive certain places as comfortable, pleasant. And it’s not just a matter of perception: those places are suitable, they make us feel good (S. Serafini, “Subcodes in linguistics and design: A comparison about biophilia and language”. Journal of Biourbanism, V, 2016).

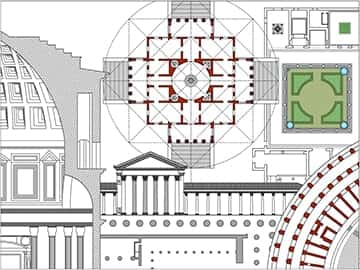

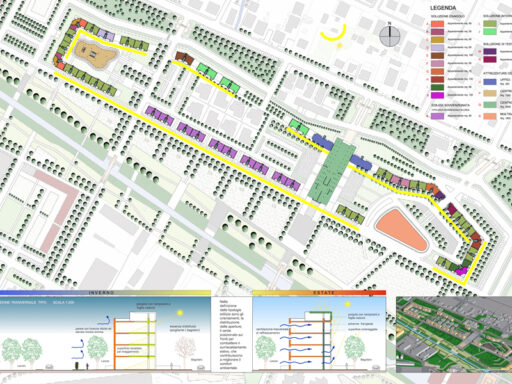

Of course the relationship is not blind. I mean that these sub-codes are connected to one end to the laws of nature, to the fact that our bodies, like the spaces in which we live, must obey precise physico-chemical constraints in order to function. But at the other extreme, the sub-codes are connected to moral and cultural codes, and here you enter an extraordinary territory, the one exposed very well by Prof. Besim Hakim that of the “biophilia” of Mediterranean architecture, for example, showed the historical genesis in the form of urban, construction and legal codes (see for example his Mediterranean Urbanism, 2014).

What is the starting point for a first evaluative analysis of the place in relation to the shape and function of a space?

The starting point is our body. How it feels, in that space. Not in theory, or in aesthetic-ideological terms, but precisely “with the belly”, with the skin, that of everyday life. If the body is well, the light that changes with the hours of the day, the way space actually works, the quality of sleep, the feeling of openness to others, the sense of protection, of peace, of inspiration to the action, as the place becomes with the changing of seasons and functions, if that place offers a center … It is difficult to define this which is also a very simple principle (letting go of our ideas, suspending judgment, as Husserl taught) because you don’t he sees but only the effects are seen.

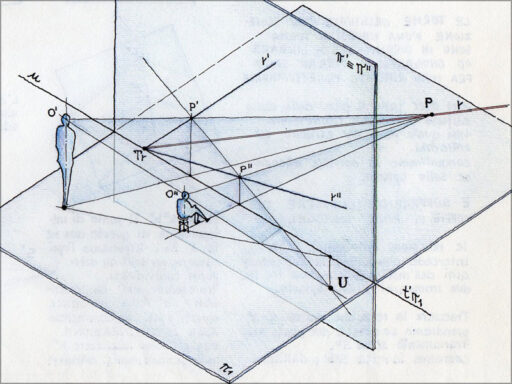

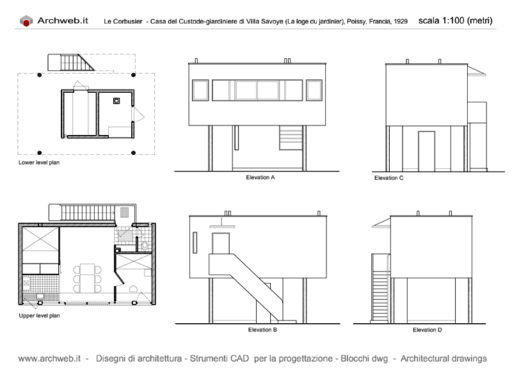

Nature as the guiding principle of geometric and functional relationships introduces the concept of Neuroergonomy in spaces: can we compare it to Le Corbusier’s Modulor?

I wanted to dedicate a summer school a few years ago to the concept of neuroergonomy. The term was then (and basically still today) used almost exclusively by the military: ergonomics adapted to reaction times in the efficient use of war instruments. For me it is a speech that is too important to be left to the bombers, because it represents the intersection point between environmental psychology, neurology and architecture. No discipline is a panacea, but used well, neuroergonomy can achieve wonderful results. If anything, the problem is to base it on correct principles.

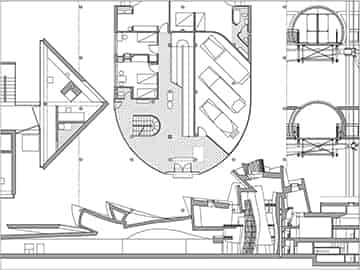

Le Corbusier Modulor was undoubtedly an important study, but it was based on a concept of external physicality which, beyond the anthropometric arbitrariness, did not take into account the way in which it works, for example, our cognitive system and how in its reaction to the environment, it involves all the other systems of which we are composed, from the endocrine to the social one. Le Corbusier himself, on the other hand, knew well that Modulor could not be used as a stencil because it had specific limits.

Based on your studies also on the historical level on the Middle Ages, could the concept of neuroscience and perception of living in time and space be linked to a wider concept of sense of appearance to a place?

Modernity has uprooted us from the enchantment of the cosmos as an entity to belong to; then from the place itself, which especially in large cities becomes uncomfortable, hostile to our corporeality, as well as being ephemeral; then, again, over time, that urban rhythms have first fragmented and then reduced to zero in the continuous relevance of the connection, a sort of black hole that absorbs all our vital time (one of the most recurring complaints of people is that of “not have time ”, especially to enjoy life).

Digitalization has finally made us all inhabitants of a flow without limits or boundaries, whose cyclicality in many respects has pushed us back to a pre-Christian era. It is modernity that devours itself, after destroying everything else. In the Middle Ages, if we want to use such a generic term, living or going home was a universal condition. Today, at best, we are tourists or refugees of our own existence and this condition is not efficient, it is not interesting whatever the accelerators or posthumanists say, because the horizon of events to which it leads us is a black afterlife that already has us condemned and exterminated.

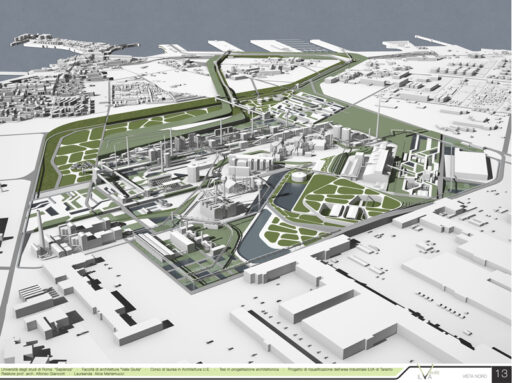

I find it bitterly funny that all the work of destruction of Western theology has led us to a black theology, to the worship of the machine. Yet I believe that architecture and urban planning attentive to this human being present here and now can propose a new path of living. I call them bioarchitecture and biourbanism.

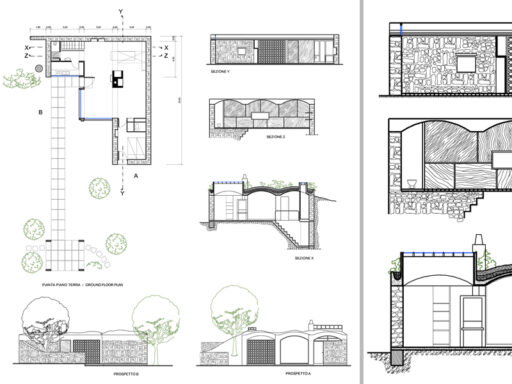

Considering the naturalistic dimension, the choice of materials on the basis of the “genius loci” and the coherence between man and nature, what is the project that you consider most complete in biophilic terms? What are your tips given your experience also in the field in contact with scholars of the sector at 360 °?

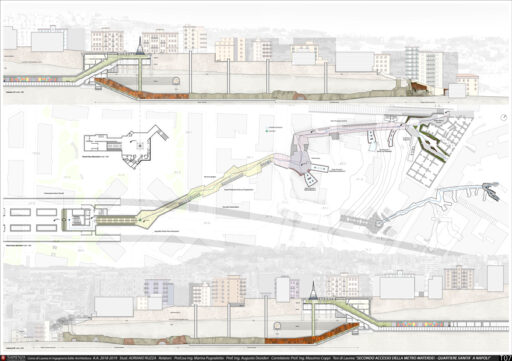

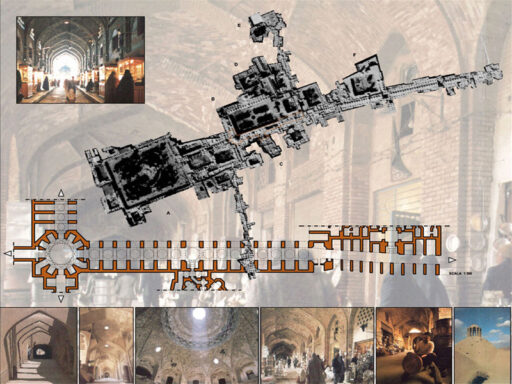

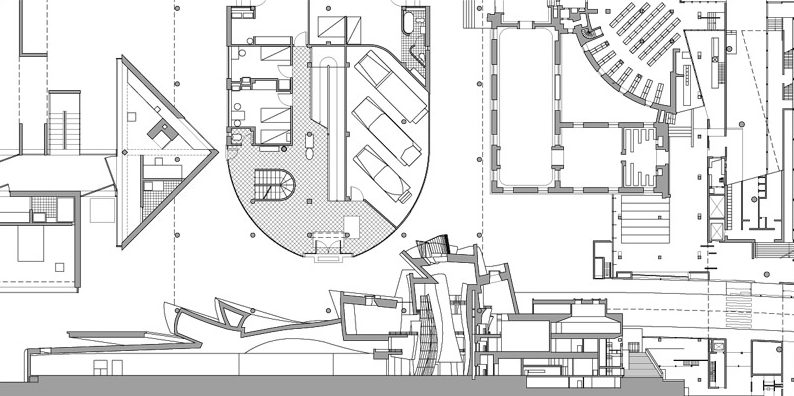

It is a difficult question, because to answer it would first be necessary to establish a context of significance. I am reminded of many things, even paradoxical ones, such as certain slums, or places reused without clamor still today by ordinary people, in Italy for example. in our internal areas, in post-Soviet monotowns, in Taipei (in 2013 I edited, by Angelo Abbate, a very talkative booklet on this subject, Biourbanism Acupuncture: Treasure Hills of Taipei to Artena, by architect and artist Marco Casagrande) . In short, in its most intense state, biophilia tends to be a state of grace typical of architecture without architects, of everyday urbanism.

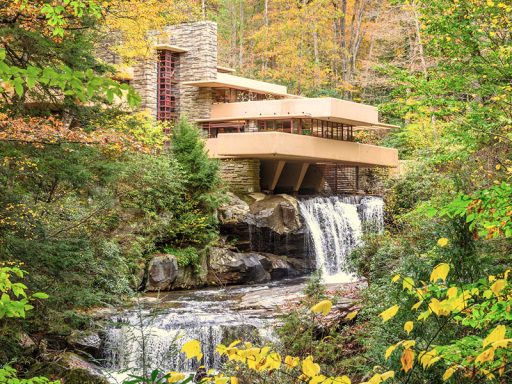

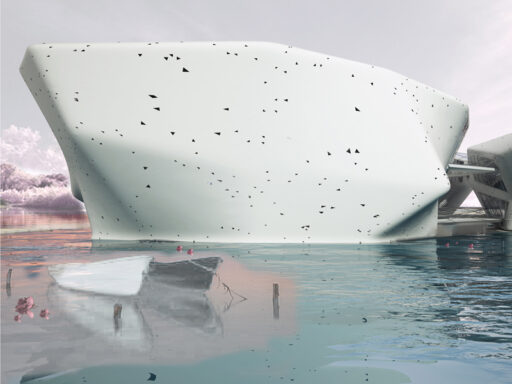

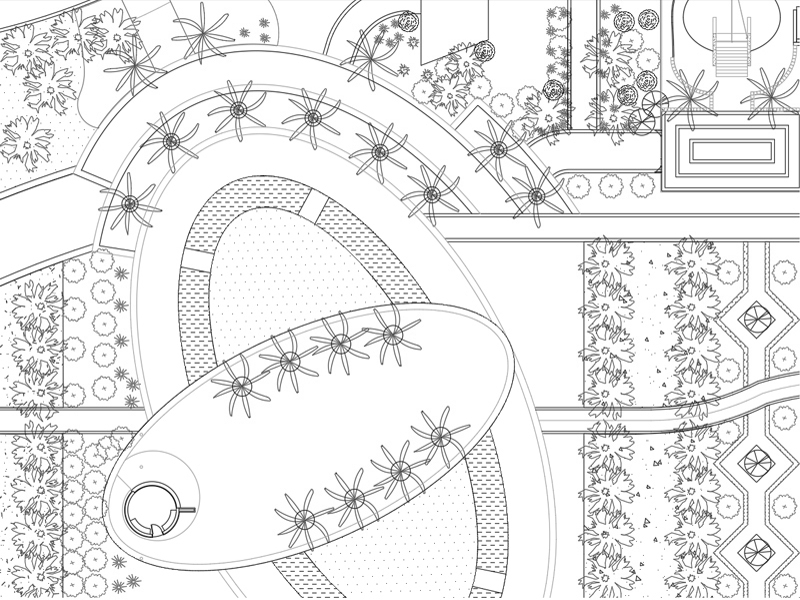

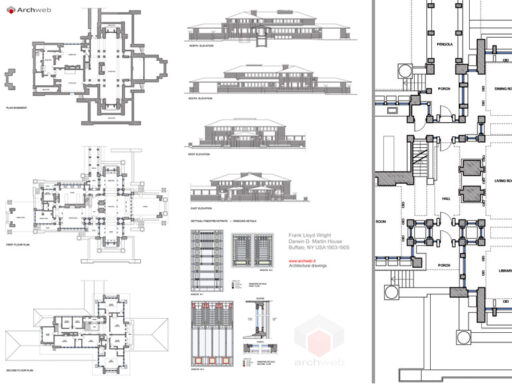

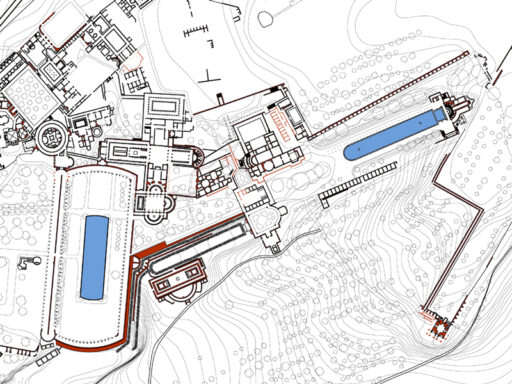

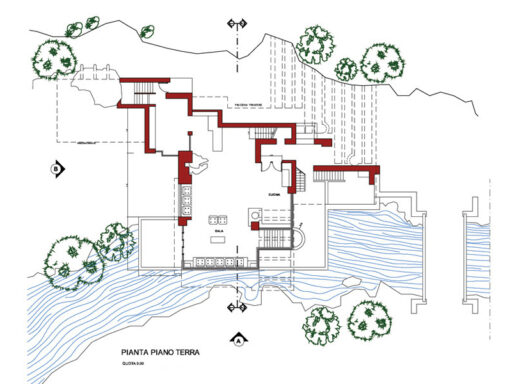

I do not consider authentic biophilia that developed by a certain American school that would like to exploit the “functional pleasantness” of design for commercial and production purposes. I find it a profound aberration of evidence based design, reduced to a horizon of a sense of profit that is radically tanatic in itself. The same goes for the clever skyscrapers covered with plants, a hypocritical, objectively false and morally abject greenwashing. On a broader level, I like heterogeneous works, ranging from the villa of Emperor Hadrian in Tivoli to Frank Lloyd Wright, from Geoffrey Bawa to Christopher Alexander, from Marco Casagrande to the Masomi Atelier.

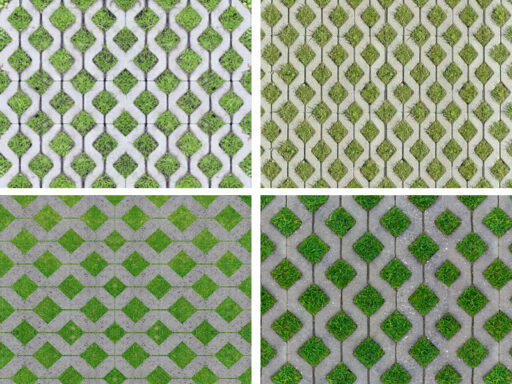

The global market places the architect before new challenges; how can a renovation project for a private house or garden be biophilic?

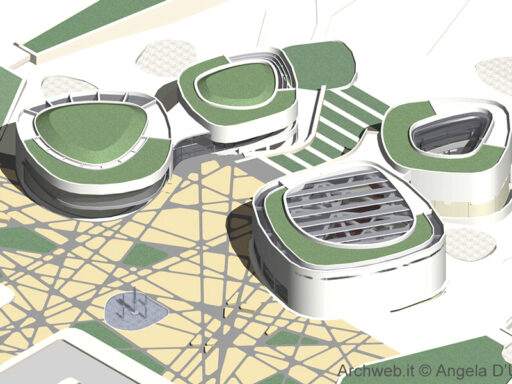

Reuse, in a certain sense, is already more biophilic in power than a new building, even more so if it involves a garden: I would say that we have already added enough weight on this poor land that supports us. For the rest, the principles do not change: connection to the body, to the living thing that inhabits the place and to the biosociosphere that supports it. Designing biophilia means deepening these terms in a dialoguing process, of feedback, of erotic love to the context.